Comments criticisms and clarifications invited.

Over to you.

Michael Smythe

digging up the artefacts that created New Zealand design history

KIWI NUGGETSTM is a series dedicated to extracting artefacts from the goldmine (or should that be minefield?) that is

Firstly, you are invited to post comments below this introduction to suggest subjects for this series - or if you prefer, contact the writer by emailing michael@creationz.co.nz

Secondly, each story will be presented as a summary of what we know and what we still want to find out. Your comments, corrections, clarifications and any new information will be most welcome.

The full text of this story The tail of the flying waka can be found in PRODESIGN 87, Feb /Mar 2007, p.78.

c.1946. Bill Haythornthwaite and George Moore designed a stylised maroro, a flying fish, logo for Tasman Empire Airways.

1965. TEAL changed its name to Air New Zealand, when it was expanding routes to North America and

1970. Air New Zealand Marketing Services Manager Bernie McEwen briefed a number of the advertising agencies to creatively consider ‘a new promotional image’. Initial recommendations were presented in November.

Dailey & Associates, Los Angeles, noted that “no one carrier presently operating in the South Pacific is doing the image job that the area connotes (romantic, exotic, Polynesia, etc), argued for retaining the blues and greens while simplifying and upgrading the existing maroro and Southern Cross and proposed the theme “The Pacific Adventure”.

Grant Advertising International, Hong Kong, recommended a strong, simple, modern Air New Zealand symbol and a visual expression of Air New

Grant Advertising, London, proposed countering "Pan Am’s 747 – the plane with all the room in the world” and “Continental 747 – the proud bird of the Pacific” with “Air New Zealand DC-10 – the

Dobbs Wiggins McCann Erickson, Wellington, saw the

Dobbs Wiggins argued the case for using a Maori motif. “No one can deny the place of the Maori in

Roundhill Studios artist Ken Chapman remembers Bernie McEwen coming to the studio with a model of the DC-10, the Dobbs Wiggins concept of a Maori waka stern post bearing a Polynesian pattern and a strong view that the teal and blue colour scheme was preferred.

1973. The first DC-10 bearing the new livery was rolled out in January to general acclaim.

It was some years later that concerns were raised by some Maori about the Air New Zealand koru as an example of cultural appropriation – probably in the lead up to placing the Wai 262 claim before the Waitangi Tribunal. Air

Anything we have missed about the Air New Zealand koru development.

Documentation or recollections relating to Maori objections and concerns about the use of Maori imagery by Air New

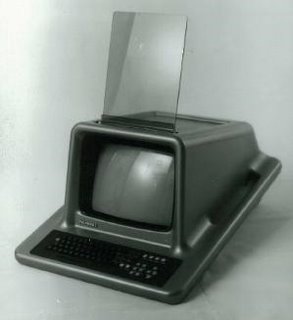

In 1980 a niche market in the education sector was recognised by Neil Scott and Paul Bryant of the

Scott was assigned to the project full-time and worked with a development team of about six engineers and technicians. 50 working prototypes were built in eight months using the leading-edge technology of the time. The Poly1 began with 64 kilobytes of memory (four times the maximum available on an Apple II) and a video card so that video was overlaid with graphics on a Philips 14” colour television monitor.

The government’s Development Finance Corporation partnered with

At the Education Department Kevin Hearle managed the production of computer-friendly course material for which Polycorp became the agents. Sixty teachers worked through the 1980-81 summer holiday to write course content into ‘shells’ created in the software. Polycorp presented their product as a reliable, robust, networked, teacher and student-friendly closed system specifically designed to deliver computer assisted learning across curricula as well as computer awareness, computer studies and support for school administration.

The Design School at Wellington Polytechnic was brought into the project to encase and express the qualities of this unique product. Tutors

The Poly1 was superseded by the Poly2 which used a boring, beige off-the-shelf box to house what was still a differentiated evolving system.

The Poly computer was at least eighteen months ahead of the Acorn BBC Micro computer that eventually dominated the education sector in the

Kiwi can-do cooperation is matched only by our cruel capacity for clobbering. The fledgling micro-computer industry set about building its market base for imported PCs by bad-mouthing bureaucrats and boffins for denying it rightful access to the state education sector. A low blow was landed when someone claimed that an early working title, ‘Polywog’ (as in tadpole), was racist.

By late 1981 when the market-ready Poly1 had completed field trials, the National government had scraped back with a one-seat majority. Behind the scenes right-wing interests were beginning to decree that government participation in the business world was not politically correct. The Government succumbed to lobbying and reneged on its purchase agreement for 1000 Polys per year for five years. Cabinet minister Warren Cooper told Perce Harpham that he and his colleagues "could see no reason why Government should spend money so that teachers could do even less work." A story soon surfaced concerning one US computer company’s New Zealand operation being headed by someone who had been a senior National minister’s campaign manager and that another ex-minister, then representing New Zealand abroad, was a major stakeholder.

Several thousand Poly1 units were sold, but the base

The DFC was declared insolvent and stopped trading in late 1989 so Progeni was on its own. About a year later, just as the Vice President of the Agricultural Bank of

Anything that expands on this story.

The whereabouts of any Poly1 Computers now.

The full text of this story Raising Dough for Denmark can be found in PRODESiGN 84, August /September 2006, p.58.

The full text of this story Raising Dough for Denmark can be found in PRODESiGN 84, August /September 2006, p.58.Artefact 1990/546 was donated to the

When Mary and Niels Nielsen arrived from

Mary decided to offer something not available in

What happened to the Booth Macdonald foundry in

Does anyone know where the original pattern, Reg 2539, might be?

What makes Mary’s enterprise even more impressive was that it got underway just as the Great Depression began. Export prices fell by 40% between 1928 and 1931. Public Service wages were cut by 10% in both 1931 and 1932. By 1932 the Christchurch Mayor’s Fund dealt with 10,000 applications per week for relief. Nationwide unemployment reached 51,000 (women were not counted) by October 1933. At that time a return trip for two to Denmark would have cost more than a year’s wages – the average weekly wage of a fitter and turner was £4/2/6 ($8.50). The

The pan design seems to date back to earlier days of cooking over open fires, hence a hoop handle which can hang on a hook. Although electric and gas stoves were in production in the 1930s, the coal range remained at the centre of many households well into the 1940s. Gas and electricity showrooms happily hosted public demonstrations of the Batter Ball Pan before Mary and her team of canvassers went from door to door. While the pan design was directly adopted from

In

Does anyone recall ‘square meals in round holes’, or anything else, cooked in these pans?

It seems that Mary’s iron casting Reg 2539 sold like hot cakes (what else?) because the return visit to

The full article on this Kiwi Nugget IT’S A TIMBER JACK AND IT’S OK is published in PRODESiGN magazine, June/July 2006, p.92.

The full article on this Kiwi Nugget IT’S A TIMBER JACK AND IT’S OK is published in PRODESiGN magazine, June/July 2006, p.92.WHAT WE KNOW and WHAT WE WOULD LIKE TO KNOW:

Exploitation of New Zealand Kauri forests began in the 1820s. The principal tool for moving logs was the handspike, a lever cut from a sapling.

The timber jack is a mechanical device which transfers the rotary motion of a double-ended handle to the longitudinal extension of a steel bar or ‘spear’, which is used to stabilise or roll very heavy logs. Does a diagram of its internal workings exist?

The earliest documentation of a timber jack we have found is an 1815 John Constable painting which shows a similar appliance in the foreground. Has any earlier record been found?

Will Robinson, a saw doctor and smithy employed at Henderson Mill, “was reputedly the first man in

A Thomas Davison saw two jacks being used for loading spars on an English ship in the Hokianga in 1844-5. He bought one but because its weight, 200lb (91kg), made it unsuitable for use in the bush he had a 60lb jack made to his design by a pioneer blacksmith named Vickery. It is not clear if the company formed later, Vickery and Mansfield, produced them in volume. Davison reported that their version was superseded by an improved design made by the Price Brothers in

Will Price, son of A. & G. Price founder Alfred, understood that the firm’s first jack was made for the manager of the Kauri Timber Company in

In spite of many references to the ‘patented Price timber jack’, no record has been found. Patent 354, filed in 1879 in the name of John McLeod, Engineer of Auckland, substitutes a ‘perpetual conical cam’ for the ordinary wheels, pinions and screws used for moving the spear. The advantages he claims include a much longer thrust, prevention from recoiling under weight and increased safety and effectiveness through its reduced size and weight. There is no evidence that these improvements went into production. The patent lapsed in 1881 through non-payment of the renewal fee. There is a drawing of what can be described as a spiral cam included in teh patent. Were McLeod’s improvements ever applied to manufactured jacks?

Will Price joined A. & G. Price in 1893. By the time he retired the firm had made over 23,000 timber jacks and production was still going strong. The example in the Waipu Heritage Centre collection has the number 21421 stamped on it, which suggests they were numbered consecutively. What is the largest number known to have been stamped on a timber jack?

The Waipu museum has been told that A. & G. Price made the timber jack by hand for many years before turning to mechanised production. This may make it one of

Was this kind of timber jack produced in volume elsewhere in the world?

CAPTION:

A&G Price Timber Jack No. 21421, steel, cast iron, kauri and many coatings of oil. Waipu Heritage Centre. Photo: Peter Davies.